Creation and Development of Battlefields Park:

- The Plains of Abraham: a space worthy of protection

- The Quebec City tricentennial celebration and the creation of the Battlefields Park

- Acquisition of premises and development of the park

- Observatory

- Jail - 1867-1970

- Quebec Skating Rink - 1891-1918

- Arsenal - 1884-1938

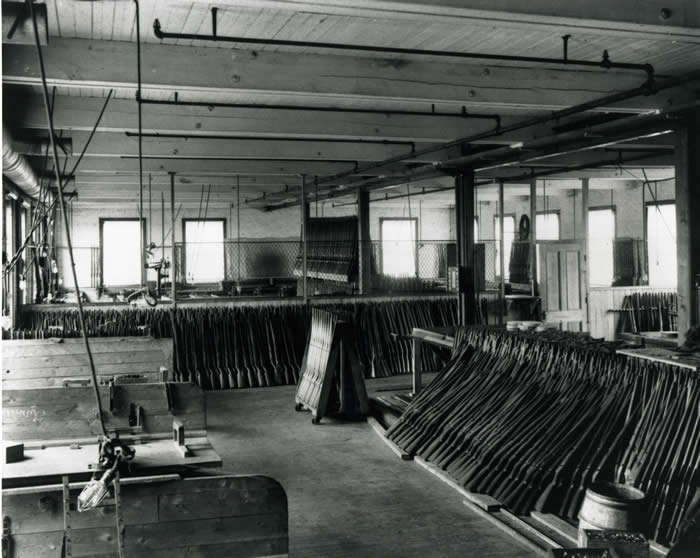

- Ross Rifle Factory - 1902-1931

- Municipal reservoir - 1931-1933

- Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec - 1933

- Soldiers' huts; prison camp; faubourg de la misère - 1940-1952

- Greenhouses

- Workshops

- 390 de Bernières

- Pavilion (Services building)

- Edwin-Bélanger Bandstand

- Plains of Abraham Museum

A Place on the Edge of Town

Now a place of assembly, commemoration, celebration and relaxation, the Plains of Abraham has a darker side to its history. Many have found death there, some gloriously, as the soldiers who fell in the battles of 1759 and 1760, and others, ignominiously. Indeed, the Plains served as the place where a number of death sentences were carried out. Also, this site on the edge of town turned out to be a favourite place for prostitution and other immoral and illicit activities.

Executions

The heights of Quebec, generally the Buttes-à-Nepveu, where the Martello Towers and the Joan of Arc Garden are found today, were the scene of 10 or so hangings for murder or theft between 1763 and 1810. One of the most famous executions was undoubtedly that of Marie-Josephte Corriveau, better known as “La Corriveau,” who was found guilty of murdering her husband and was hanged on theButtes-à-Nepveu on April 18, 1763. Her remains were exposed for about 40 days in a cage at Pointe Lévy for the edification of passers-by from la Côte-du-Sud. The story has inspired many legends over more than two centuries.

La Corriveau.

Credit: Bronze statue by Alfred Laliberté, Musée national des beaux-arts de Québec.

A large crowd witnessed the execution of David McLane, found guilty of high treason, on July 7, 1797. The gallows were set up “on les Glacis, outside the walls of the city.” [translation] McLane was told that he was sentenced

[…] to be hanged by the neck, but not until death. You must still be alive, while your entrails are cut out and burned before your eyes; then your head will be separated from your body, which will have been quartered; and your head and limbs will be at the disposition of the King.

Fortunately for the condemned man, his head was apparently severed before the tearing out of his entrails. Others, such as Alexander Webb on June 15, 1784, were even more fortunate, and were spared at the foot of the gallows.

More than 10 condemned people were hanged at the Quebec City prison on the Plains between 1867 and 1937. A crowd of about 3,000 assembled on January 10, 1879, for the first execution, that of convicted murderer Michael Farrell. The scaffold was erected in the courtyard but could be seen only by a small number of witnesses: journalists, medical students, family members, and so on. The crowd had to gather around the prison to try to see what was going on. A black flag was raised when the sentence had been executed.

The setting for subsequent executions was similar. A second hanging, that of Nathaniel Randolph Dubois, found guilty of a quadruple murder, took place in 1890. On July 6, 1900, the gallows was blocked off on two sides to block out curious onlookers. Those who did witness the hanging of David Dubé were shocked to see a botched effort in which the victim agonized for 11 minutes before expiring. The Quebec prison’s final execution took place on July 9, 1937.

Prostitution and vagrancy

Like other parks in the world, the Plains acted as more than a place of relaxation for high society. For the greater part of the 19th century, its vacant land offered refuge for all kinds of social misfits. In 1801, the number of prostitutes in the city was estimated at between 500 and 600. In 1833, the Governor General received complaints that drunkards and “women of poor repute” were engaging in “the most unrestrained debauchery” there. In the mid-19th century, a number of brothels were located on the approaches to the Plains of Abraham, close to the place where the prison would be built in 1867. The Wolfe Hotel was reputed to be a bawdy house at that time. No fewer than 15 or so such establishments were found in the Saint-Jean-Baptiste district, close to the Plains. They were a popular destination of sailors, who would cross the Plains using the paths and stairways.

The main clients of the prostitutes, taverns and gambling houses were the many soldiers and sailors posted to Quebec City. One third of the mortality in the British army in the mid-19th century was attributed to venereal disease. After the decline of the port in mid-century and the departure of the British garrison in 1871, the prostitutes redoubled their soliciting efforts, to the point where they would sometimes interfere with military manoeuvres on the Esplanade.

Other misfits also found their way to the Plains of Abraham. As early as 1806, the Ursulines complained of delinquents damaging their property. In the 1830s, city residents complained on a number of occasions about activities on the Plains. In 1837, it was noted that:

The Plains of Abraham and the surrounding wooded areas, especially those of Cap-Rouge, are the regular meeting place of a working-class group of people who desire no longer to work but to live off others; … In the spring, when prisoners are released, and when shipping brings immigrants from various places to our shores, this band of miscreants spreads throughout the open areas and daily adds to its number habitual criminals, restless soldiers, adventurers, ne’er-do-wells and debauched persons. [translation]

In the 1830s, a band of brigands under the leadership of Charles Chambers was organized in Quebec City. Its members specialized in all kinds of theft, ranging from petty breaking and entering to stealing logs from the coves around the city. The Plains of Abraham afforded them an ideal place in which to hide it and recruit new members. Charles Chambers was found guilty of theft in 1837 and was deported to Australia.

Despite the organizing of a police force, these kinds of activities continued into the 20th century, although with some abatement. After the park was created, order was maintained on the Plains by the municipal police (until 1948) and by the National Battlefields Commission. The Commission hired four special constables in 1913. Most of the offences during the 20th century were related to highway safety, although “immoral” conduct still accounted for many police interventions—the removal of 392 people in 1942, for example. A few years later, in May 1948, the RCMP assigned five or six officers to maintain order on the Plains. In 1953, 1,159 couples were stopped for “inappropriate” conduct. Since then, a considerable effort has been put forth to make the Plains one of Canada’s safest parks.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900”, in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 170.

“Quebec, mercredi 16 juillet,” Gazette, July 27, 1797, p. 3.

Quoted by Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900”, p 168.

“Quebec, mercredi 16 juillet,” Gazette, July 27, 1797, p. 3.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900”, p. 168.

Lorraine Gadoury and Antonio Lechasseur, Persons Sentenced to Death in Canada, 1867-1976: An Inventory of Case Files in the Fonds of the Department of Justice. Government Archives Division, National Archives of Canada, 1994.

John, Hare “La population de la ville de Québec, 1795-1805”, Histoire sociale = Social History, Vol. VII (No. 13), Mai-May 1974: 35.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900” p. 171.

“Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900”

François Boulianne, La répression de la prostitution à Québec : discours, institutions et application, 1850-1870, Quebec City: Université Laval, [Masters thesis awaiting submission].

John Hare, Marc Lafrance and David-Thierry Ruddel, Histoire de la ville de Québec, Montreal: Boréal/Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1987, p. 208.

F.-R. Angers, Les révélations du Crime ou Cambray et ses complices, Quebec City: Fréchette et cie, 1837, p. 30-31.

F.-R. Angers, Les révélations du Crime ou Cambray et ses complices, p. 10.

Archives of the National Battlefields Commission, Minutes of Board of Directors Meeting of November5, 1942.

Archives of the National Battlefields Commission, meeting of November 23, 1953.

Creation and Development of Battlefields Park

Battlefields Park, the pride of Quebec City, is celebrating its hundredth anniversary in 2008. Created as part of the tricentennial celebrations, the park’s original purpose was to give residents and visitors a green space in the heart of the city, and to preserve and commemorate the site of the battles of 1759 and 1760 between British and French.

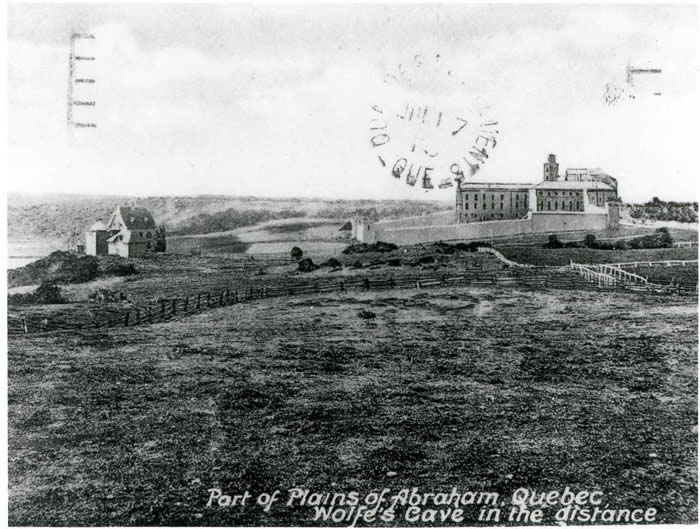

The Plains of Abraham: a space worthy of protection

Quebec was not only the colony’s political and administrative capital, it was also a very important economic centre in the 19th century. The preferential tariffs on imports from the North American colonies applied by London in 1795, and the continental blockade established by France in 1806 accentuated trade relations between the metropolis and Canada. Drawn by this economic vitality many immigrants, including a large percentage of Irish, moved into the capital. The population grew quite rapidly, placing heavy pressure on urban development. In the Upper Town, this led to a desire to occupy and in fact to subdivide some vacant pieces of property, chief among them the Plains of Abraham.

The city was characterized increasingly in the 19th century by social stratification. Workers, craftsmen and day labourers lived primarily in the suburbs of the Lower Town and in some districts of the Quebec promontory, while the rich merchants, administrators and military officers preferred the attractions of the properties along the Grande-Allée and atop the cliff. The popularity of the latter sector led to an increasing demand for the subdivision of open areas, especially since the military presence, which had long hampered urban development, would soon be coming to an end.

In a sense the departure of the British troops from Quebec City in 1871 marked the end of the army’s monopoly over the best property. For strategic reasons, the military had long taken pains to maintain control of the land near the fortifications and thereby minimize urban development close to its defensive works. The army controlled the Cove Fields and leased the Plains of Abraham from the Ursulines; this comprised the land between what is now the Musée national des beaux-arts de Quebec and the Marchmount (now Mérici) Estate.

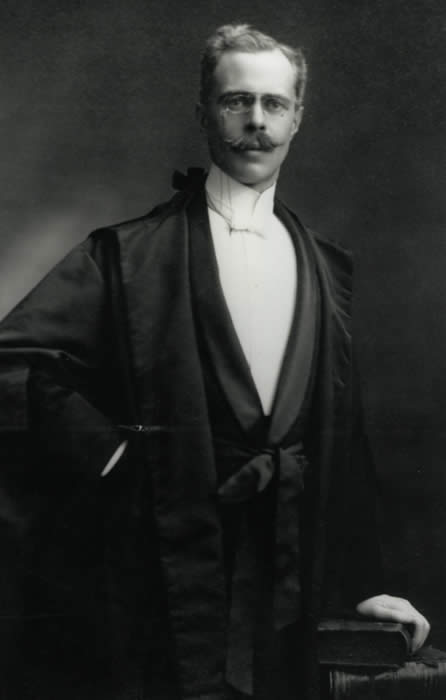

Map showing the Cove Fields site.

Credit: Plan of the City of Quebec and Environs, 1891, LAC.

Land speculation was rife with the relaxation of Quebec City’s defensive function. As early as 1876, some promoters suggested subdividing all of the land extending out from the base of the Citadel. The attraction of the Grande Allée also grew with the construction of the parliament building between 1877 and 1886. Finally, the army’s, and then, after 1871, the federal government’s lease from the Ursulines expired in 1902. With the Ursulines’s plans to subdivide their land, voices were raised calling for the site’s preservation. One of the ideas raised was the creation of a public park.

Like many European cities that were opening royal gardens to their citizens, and some American cities that were setting aside green spaces, Quebec wished to create a public park to provide green space for its residents. Very much in vogue in the 19th century were parks in urban areas, including Quebec, designed to make nature accessible to city dwellers. Moreover, the still vacant pieces of property at the entrances to the city were of major historic significance. As the theatres of the battles of the Plains of Abraham (1759) and Sainte-Foy (1760), they constituted memorial sites that must not be lost.

While the idea of creating a park on the site of the Plains of Abraham was not new in the late 19th century, it gained ground very swiftly in the minds of the public. People mobilized and made representations to the authorities. The Literary and Historical Society of Quebec launched a campaign to preserve the Plains. This pressure produced results on September 20, 1901, when, after lengthy negotiations, the federal government agreed to purchase the Plains of Abraham from the Ursulines for the sum of $80,000. At the time, the territory was limited to the land between the current Musée national des beaux-arts du Quebec and the Mérici Estate. The land would then be handed over to the City of Quebec the same day by an emphyteutic lease. In addition to the purchase price, the Ursulines received the Marchmount (Mérici) property and asked that it be transformed into a public park. All that remained was to actually create the park. And while the degree of development was rather modest in the early years—a few trees were planted and a few paths were made—all would be changed by one event—the upcoming Quebec City tricentennial celebration.

The Quebec City tricentennial celebration and the creation of the Battlefields Park

p>With the approach of the tricentennial of Quebec, some of the city’s notables felt that a grandiose celebration was in order. One of the first to move in this direction was attorney and city clerk Honoré-Julien-Jean-Baptiste Chouinard. In late 1904, in the Christmas issue of the Quebec Daily Telegraph, Chouinard wrote an article discussing why he felt that all Canadians, regardless of their roots, should feel a kinship with this event. He also made a few practical suggestions, including rebuilding the city gates, building terraces, esplanades and lookouts, restoring the fortifications, building a historical museum, creating parks, etc.

The response to Chouinard’s efforts did not come until March 1906, 15 months later, by way of the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society (SJBS), of which he was a very active member. Addressing the society’s executive council, he stressed the need for urgent action. In his mind, the initiative of organizing celebrations to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Quebec City should naturally be taken up by Quebec’s national organization. While the Society agreed, it alone did not have the resources needed to organize such an event. Thus it was decided that while the Society should take the initiative for the project, it must look beyond French Canada to Canada at large, in order that another organization might raise the support, primarily financial, from the rest of the country.

The responsibility was then transferred by the SJBS to the Quebec City municipal government. George Garneau, the Mayor since February 1906, promptly formed a tricentennial committee, which heard Chouinard’s proposal on May 14 of the same year. Doubtless spurred on by the enthusiasm of his colleagues, Chouinard put forth a rather detailed and highly ambitious proposal calling for infrastructure renewal, commemoration of the 1608 founding (massing of warships in the port, reconstruction of Champlain’s “Abitation,” wearing of period costumes, etc.), historic reenactments and processions depicting the early colonists, coureurs de bois, soldiers of the English and French regiments of 1759-1760, and more. The Mayor and his team were convinced that the project would cost more than a million dollars and must draw upon the resources of the federal, provincial and municipal governments.

Led by Mayor Garneau, the municipal authorities saw a tricentennial celebration as an excellent means of improving the city’s infrastructures and stimulating its economy. They supported Chouinard’s plan unreservedly and got down to work. Six committees were formed to take care of various facets of the job. One of them would be responsible for providing advice on the purpose and nature of the celebrations. The Historical and Archaeological Commission, as it was called, consisted of experts in history, namely Judge François Langelier, Deputy Minister of Lands and Forests and renowned architect Eugène Taché, and Colonel William Wood, a specialist in the Seven Years’ War and former president of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec. They tabled a report in 1907 exhorting the municipal authorities to take action to beautify the city and to preserve and enhance its historic attractions. They recommended creating a park extending from the walls of the Citadel to the property of the Ursulines (the Mérici estate) and stretching to the Des Braves monument on chemin Sainte-Foy. They also suggested building a promenade joining this monument to Quebec City along coteau Sainte-Geneviève.

While the committees were doing their work, Garneau and his team began lobbying Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the Liberal Prime Minister and Member of Parliament for Quebec East. As leader of the country since 1896, Laurier had since coming to power been subject to pressure from Anglophone imperialists on the one hand and Quebec nationalist anti-imperialists on the other. He must therefore walk a fine line and watch appearances knowing that many imperialists felt that his province had already received much from the federal government. Garneau too had to tread carefully amidst this tension between imperialists and nationalists. This he understood very well. The first delegation to the Prime Minister’s office in June 1906 was bicultural and bidenominational. In addition to Mayor Garneau, it included the rector of St. Matthews Anglican Church, a representative of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec and Chouinard, as Secretary.

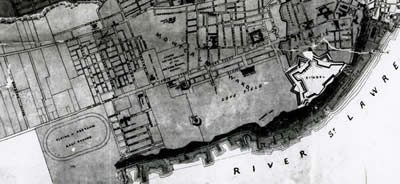

Rt. Hon. Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Prime Minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911.

Credit: Photo by James William Topley, 1906, LAC.

Another major player contributing to promoting the importance of the tricentennial celebration was Canada’s Governor General, Lord Grey. He was a strong advocate of the creation of a commemorative park in honour of the memory of the British and French combatants of 1759 and 1760. His project was similar in some respects to the recommendations of the Historical and Archaeological Commission, but he went even farther, proposing the erection of a huge statue 30 centimetres taller than the Statue of Liberty, depicting the Angel of Peace. He also suggested that buildings such as the observatory, the prison and the armoury, that might obstruct the creation of the park, should be destroyed. With this in mind, he set a goal of amassing close to $2 million to finance his dream.

Negotiations between the City of Quebec and the federal government finally ended in April 1907 when Laurier committed his government to a contribution of $300,000 for the tricentennial celebration, provided that the money be placed under the authority of a federal commission and that Quebec province agree to make a significant contribution of its own. The Quebec government involvement would amount to $100,000, and would be used strictly to purchase and develop the Battlefields Park. The contributions made by the other provinces would be used for the same purposes. These contributions were the fruit of the efforts of Lord Grey, who had seen that the governments of Laurier, Gwynn and Garneau—the federal, provincial and municipal governments—could not finance his ambitions on their own, and ranged from $2, 500 to $10,000, with the exception of Ontario’s, which matched Quebec’s $100,000.

The die seemed to be cast for the tricentennial celebrations by the spring of 1907. Owing to various constraints on Laurier’s part, the legislative provisions for officializing them had to wait until early 1908. Accordingly, the Prime Minister suggested deferring the celebration until 1909, the date of the planned inauguration of the Quebec Bridge. The Mayor and Council accepted this proposal.

These plans were thrown into tragic disarray with the collapse of the Quebec Bridge on August 29, 1907, leaving the city in a state of consternation. Laurier also, who had planned to defer the tricentennial celebration, was deeply demoralized. In his mind, the festivities and the inauguration of the bridge were so closely tied together that one could not take place without the other. Alarmed, Garneau responded with a reminder to the Prime Minister of the political cost that he risked incurring by cancelling the event. Grey also applied pressure, trying to convince Laurier to publicly announce the funding campaign that he was preparing to launch throughout the British Empire. He also pleaded for a return to the original idea of holding the festivities in 1908, the anniversary of the actual founding of Quebec City.

Laurier finally acquiesced in the face of the pressure from Garneau and Grey, from nationalists and imperialists alike. He would follow through on his financial commitments and would table in Parliament a bill to create the commission responsible for organizing the tricentennial celebrations.

The Act creating the National Battlefields Commission was finally tabled on March 3, 1908, and was assented to on the 17th of that month following a brief debate. The composition of the Commission reflected Laurier’s desire to protect himself politically. George Garneau was named Chair, a natural choice given the latter’s involvement in the tricentennial project. The choosing of the commissioners was also strategic: one was a nationalist and another, a financier from Quebec; one was an imperialist and another, an Ontario financier. Their names were Adélard Turgeon, the new Chair of the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society of Quebec; George Drummond, a member of the Montreal financial community; Colonel George T. Denison, an attorney, militia officer and Toronto police magistrate; and Edmund Walker, President of the Canadian Bank of Commerce. The law also stipulated that provinces making generous contributions could also be represented by a commissioner. As things turned out, only Quebec and Ontario, with their contributions of $100,000 each, attained this status. The latter’s donation was reflected in the naming of Ontario Avenue, one of the prettiest thoroughfares in the park

The purpose of creating the Commission was twofold: to organize the tricentennial celebration, and to create a public park where the battles of 1759 and 1760 took place. Laurier expressed it in this way in the House:

One idea is to have a celebration, the second is to acquire, at the earliest possible moment, this land reclaimed in order to consecrate it as national property forever, that it may be placed in our hands and not be used for anything else.

In addition to the contributions of the various governments, the Commission could rely on the funding campaign conducted by the Governor General to create the Battlefields Park. He endeavoured to secure the participation of Canadians and of the British Empire at large, but met with only moderate success, raising about one quarter of the two million hoped for. Thus Lord Grey had to relinquish his idea of the Angel of Peace statue. The amount raised was nonetheless very useful in the park’s development. As for the tricentennial celebrations, the Commission had no time to lose. The official launch was scheduled to take place four months later, during the visit of the Prince of Wales on July 22.

As the celebration drew near, time and money were not the only factors jeopardizing its success. A number of nationalists conducted a campaign opposing the celebration which, in their minds, represented a commemoration of the British conquest rather than the founding of Quebec. The park would be commemorating the victory of Wolfe rather than the work of Champlain. The nationalist rationale had a significant impact on the French-Canadians, who now had reservations about the project. The Church and influential people such as renowned historian and politician Thomas Chapais had to intervene to temper the radical discourse of certain nationalists. A successful tricentennial celebration would benefit the city and its people, they said, adding that Champlain, not Wolfe, would be the leading figure. Furthermore, Quebec must not turn down the gift of a national park.

As it turned out, large numbers of French-Canadians participated in the event, which also attracted many visitors. They attended the feature events and contributed in their own way by wearing costumes and decorating their residences and businesses. The two-week-long festivities were a success. The Commission’s primary objective had been met, and it was now time to begin creating and developing the Battlefields Park.

Acquisition of premises and development of the park

Purchasing the property that would enlarge the Plains of Abraham beyond its 1908 confines was a gradual process. From east to west, the Commission must acquire:

- Cove Fields, which belonged to the Ministry of Militia (now National Defence);

- some private property, including an old Séminaire de Québec farm and a landlocked parcel on the farm belonging to the Dominicans;

- property belonging to the Quebec government on which the prison was built;

- subdivided property close to the Des Braves monument;

- part of the Ursulines (Mérici) property for the construction of an avenue extending côte Gilmour by connecting chemin Saint-Louis and l’Anse-au-Foulon (now rue De Laune).

It was not all smooth sailing. Negotiations with the Quebec government for the prison grounds ended in 1911, with a reservation included concerning the building and a part of the property; the Commission had to litigate when it became impossible to come to terms with the Seminary, the Dominicans and the owners of the properties close to the Des Braves monument. Negotiations with the Ursulines, which began in 1912, dragged on until 1926; finally, National Defence would not agree to give up Cove Fields until 1928.

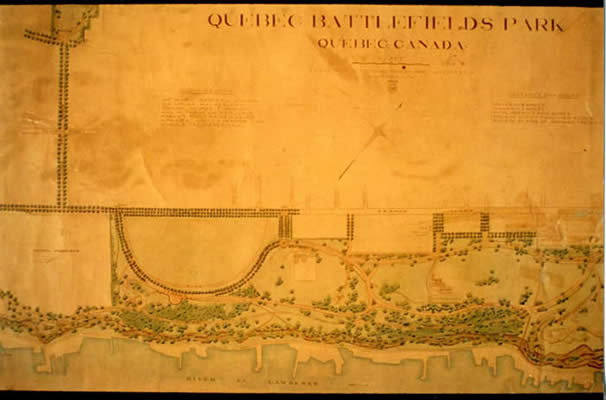

Very soon after its creation, the Commission had to prepare a development plan for the park in conjunction with the property acquisitions. This task was assigned in May 1909 to landscape architect Frederick G. Todd. Todd proposed creating a national park that would ensure the historic site’s permanent restoration and conservation while enhancing its beauty and splendour. Todd’s idea was to embellish what already existed, bringing out nature’s best and most attractive aspects. A landscape architect is like a painter who combines the most attractive elements on a canvas to create an overall impression pleasing to the eye. In a sense, Todd’s was a quest for the ideal. The challenge facing him was to achieve a harmonious blend of space and time and of places and their history.

Todd’s development plan was divided into five major zones each treated in accordance with their nature and their history:

- The first zone covers close to half of the park’s area and extends from the fortified enclosure to the present Museum building. The architect proposed building an avenue along the fortifications and the old earth retrenchments, now commonly known as the temporary citadel. This avenue would lead to the top of cap Diamant, which affords a very impressive view of the park and river. He also suggested restoring Martello Towers 1 and 2. Finally, he suggested preserving the natural landscape in this area: This portion of the park I have endeavoured to keep as natural and informal as possible, and at the same time have avoided planting trees, in order that it remains as nearly as possible in the condition in which it was when the historic battles took place. In fact, the only planting which is suggested is here and there a tree or group of trees along the drives and walks, to break the monotony, and groups of trees massed along the outskirts or the park in order to screen out what may be objectionable private property .

- The second zone corresponded to the old equestrian area in front of the Museum. The plans called for this property to remain flat and possibly to continue to be used for military parades, physical exercise and performances. Todd planned to build a terrace on the south slope of the hill (now Grey Terrace), where Lord Grey’s Angel of Peace would be erected.

- The third zone was a strip of land joining promontory to Anse-au-Foulon: Considered from a landscape point of view this is a charming spot, with its gentle undulating topography extending to the steep cliff and open groves of lofty Pine and Elm, while historically it is of the greatest interest, as it was up this steep cliff in the shelter of the small point of land that the General Wolfe and his advance guard climbed and put to flight the small French post encamped at the head of the road leading up from the Cove, thus gaining the key to the Plains above .

- The fourth zone, situated along the steep incline and the cliff on the south slope (Ontario Avenue sector) is the space that Todd wished to leave in its natural state to allow natural species to grow freely. "Only a few paths would be laid through it, and dangerous cliff areas would be fenced off".

- The Des Braves Park, site of the old Dumont Mill, where the fiercest fighting took place in the battle of St. Foy in 1760, won by the French army, was the fifth zone. Todd suggested linking Des Braves Park to the Plains of Abraham by an avenue (what is now Des Braves Avenue).

The landscaping plan for the Plains of Abraham submitted by F.G. Todd in 1909. It took fifty years to complete.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Todd’s plan also contained many details:

[Todd] sought to locate the Blockhouse built by Murray in 1760. He planned to identify the well where water was drawn for Wolfe as he lay dying. Plans for the lookouts and monuments were drafted. The cannons were arranged to draw attention to the site’s strategic value. The cliff in the wild state lay alongside a regular arrangement of planted growth, coupled with crisscrossing vertical drops and intersecting oval avenues. [translation]

The landscape architect submitted his report on November 15, 1909. The commissioners were impressed and adopted it immediately, with only slight modifications. A federal government grant of $100,000 was provided to start the work. However, progress was very slow.To begin with, the property acquisition phase was long and difficult. The desired areas, which included the Ross Rifle Company and laboratory, the cartridge factory, a firing range, the prison, an astronomical observatory, houses along the avenue leading to the Wolfe monument, a skating rink at the place planned for the park’s east entrance, and a golf course, presented a number of issues. Complicating things further was the political baggage of the first and second world wars. Todd’s development plan would eventually take more than 50 years to complete. However, even today it remains the reference point for work done on the Plains.

Works in the Cove Fields area in 1936.

Credit: W.B. Edwards, Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Todd’s original plan was also altered by a few events as the park was being developed. Among these was the construction of the underground water reservoir close to Martello Tower 1 from 1931 to 1933 as a result of negotiations with the City of Quebec. This transformation created a flat space contrasting with the undulating terrain of the rest of the park. Another event created a thorny problem for the Commission. Smitten by the charms of Quebec City, an American artist and her husband presented a statue of Joan of Arc on horseback as a gift. How could the presence of the French heroine, the bitter adversary of the English, be justified in a park whose purpose was to symbolize rapprochement between French and English Canadians? Thomas Chapais, the acting Premier of Quebec, justified the monument on behalf of the Commission at the official inauguration in these words:

Patriotism and valour! In other words, in bronze and granite, this monument is the glorification of heroism, personified in one of history’s most illustrious figures. Were not these historic grounds the site of one of heroism’s brightest episodes? Just a few steps from here, one hundred and seventy-nine years ago, two illustrious warriors shed their blood for their countries, and by their sublime dedication, Wolfe and Montcalm, the conqueror and the conquered, together entered the pantheon of history... Before us is the link between the two apotheoses—that of Joan of Arc and that of the two heroes of 1759. [translation]

To provide a suitable setting, the Commission created a garden along Laurier Avenue with the statue in its midst. While its elongated octagonal shape is reminiscent of a French garden, its density and variety of plants follows the English pattern. The Joan of Arc Garden was inaugurated on September 1, 1938.

Today the National Battlefields Commission is still the park’s administering body. Following in the footsteps of Sir George Garneau, Lord Grey, Frederick G. Todd and many others, today’s commissioners and employees are constantly working to improve the Battlefields Park or, alternatively, the Plains of Abraham, one of the world’s finest urban parks.

Biographies

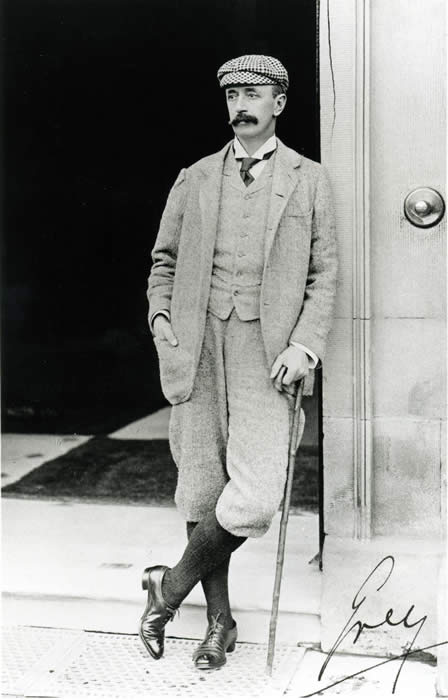

Albert Henry George Grey, 4th Earl Grey

Lord Grey was born in London on November 28, 1851. He was raised in the Court of St. James’s, since his father was Principal Secretary to Prince Albert and later to Queen Victoria. The young aristocrat studied at Trinity College, Cambridge. Having acquired an interest in politics, he was a member of the House of Commons from 1880 to 1885. In 1904, he was appointed Governor General of Canada by the government of Arthur James Balfour, replacing Lord Minto. Since the latter had been quite unpopular among the French Canadians, Lord Grey was mandated to continue conducting an imperialist policy while trying to reconcile imperialists and nationalists, who had grown farther apart in the wake of the Boer War. His involvement in organizing the tricentennial celebration and in creating a commemorative park bears witness to his efforts to fulfill this mandate.

Sir Albert Henry George Grey, General Governor of Canada from 1904 to 1911.

Credit: Lord Grey (1851-1917), LAC.

Even before the creation of the National Battlefields Commission in March 1908, Lord Grey had been preparing a funding campaign that would have given the celebration an imperialist aspect; this brought a number of criticisms from nationalists such as Henri Bourassa. Although the results of the campaign were rather disappointing, it nonetheless greatly influenced the philosophy of the tricentennial celebration. As Prime Minister Laurier had also desired, the celebration must be inclusive, involving both Anglophones and Francophones, and descendants of both the conquerors and the conquered of 1759. Grey’s task was to reconcile the two founding peoples in a celebration of the Empire.

Grey continued as Governor General until October 1911. He died at his estate in 1917.

Sir George Garneau

The son of Pierre Garneau, a prosperous merchant and industrialist and Mayor of Quebec City between 1870 and 1874, George Garneau was born in 1864. A graduate engineer of Montreal’s École Polytechnique in 1884, this son of a Liberal family was interested more in business than in politics during the early years of his working life, and did not turn his attention to the adventure of politics until the early 20th century.

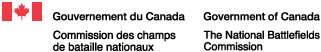

Sir George Garneau [Around 1905].

Credit: Ville de Québec.

George Garneau took up his new duties as Mayor on March 1, 1906, around the same time that the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society decided to support Jean-Baptiste Chouinard’s proposal concerning the Quebec City tricentennial celebration. A short few months after taking up his duties, the new mayor took an interest in and agreed to support the project. This began a period of intense negotiations between Garneau and his political counterparts in the provincial and federal governments. Garneau’s leadership role induced Prime Minister Laurier to appoint him Chair of the National Battlefields Commission created in 1908, the first mandate of which was to organize a celebration commemorating the tricentennial of the founding of Quebec City. As the main architect of this commemorative event’s success, he was made Knight Bachelor by the Prince of Wales on July 23, 1908, and Member of the Legion of Honour by the French government. Although he left his position as Mayor on March 1, 1910, Garneau would lead the Commission until 1939, thus leaving his imprint on the history of the National Battlefields Commission and, in a sense, on the Plains of Abraham. Sir George Garneau died in 1944 and was buried at Belmont Cemetery.

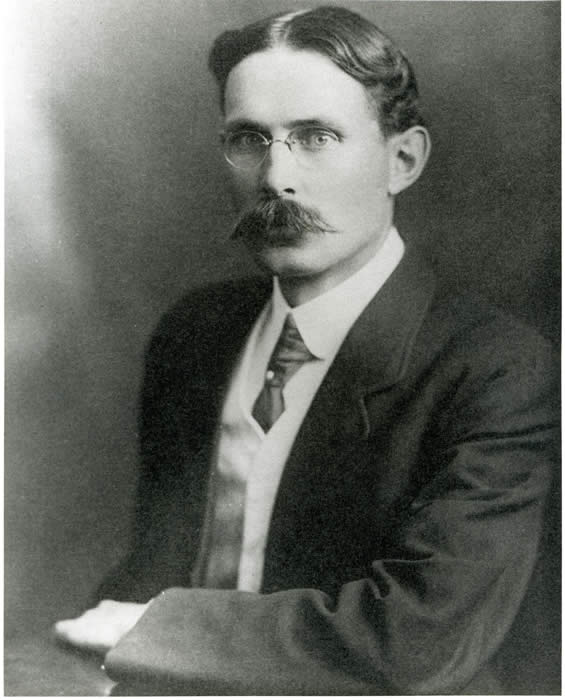

Frederick G. Todd

“Born in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1876, Frederick G. Todd was educated in Boston and trained in the offices of Frederick Law Olmstead, the pioneering landscape architecture and designer of Mount Royal Park in Montreal. […] Todd left Boston for Montreal in 1900, becoming the first landscape architect in Canada.

Three years later, he was hired by the commission responsible for the beautification of Ottawa to undertake a study on organizing parks in the capital. In 1905, he proposed to the City of Montreal a plan to refurbish the chalet near the belvedere on Mount Royal. When he was hired by the National Battlefields Commission, Todd was already involved with parks projects all over Canada. In 1912, he designed Bowring Park in St. John’s, Newfoundland. In Quebec, he later created parks in Valleyfield and Granby.

In 1936, during the Great Depression, the government of Quebec undertook major work projects to combat unemployment. In this context, Todd realized two projects that he had submitted to the City of Montreal in 1931: he created Beaver Lake, on Mount Royal, and refurbished St. Helen’s Island. He then proposed to create a huge sports centre for the Olympic Games, to be situated in Maisonneuve Park (today Olympic Park).

From the beginning of his career, Todd was also known as an urban planner; in 1908, he worked on plans for the town of Point Grey, British Columbia, but he is best known for the “model city” he designed in 1938, which became the Town of Mount Royal. Between 1945 and 1948, when he died, Todd realized his last work, The Stations of the Cross gardens near St. Joseph’s Oratory in Montreal.”

F.G. Todd, landscape architect, designer of the landscaping plan for the Plains of Abraham.

Credit: McCord Museum.

H.V. Nelles, The Art of Nation-Building: Pageantry and Spectacle at Quebec’s Tercentenary. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999, p. 47.

H.V. Nelles, The Art of Nation-Building: Pageantry and Spectacle at Quebec’s Tercentenary, pp. 52-53.

H.V. Nelles, The Art of Nation-Building: Pageantry and Spectacle at Quebec’s Tercentenary, pp. 57-58.

H.V. Nelles, The Art of Nation-Building: Pageantry and Spectacle at Quebec’s Tercentenary, pp. 59-60.

Lord Grey planned to erect the Angel of Peace statue on what is today Grey Terrace, named after him

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, p. 213.

It was politically important to show that no money raised from public subscription went to finance the festivities but to purchase and develop the Battlefields Park. See H.V. Nelles, op. cit., p. 375.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, p. 213.

Wilfrid Laurier addressed the House of Commons on March 3, 1908. Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada - Fourth Session, Tenth Parliament - Volume LXXXIV - Ottawa, 1907-1908, pp. 4383-4384.

H.V. Nelles, The Art of Nation-Building: Pageantry and Spectacle at Quebec’s Tercentenary, pp. 374-375.

Frederick G. Todd, Report from Frederick G. Todd on the Plans for the National Battlefields Park, submitted on November 15, 1909; stored in the National Battlefields Commission archives.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, p. 218.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, p. 216.

Frederick G. Todd, Report from Frederick G. Todd on the Plans for the National Battlefields Park, p. 3.

Frederick G. Todd, Report from Frederick G. Todd on the Plans for the National Battlefields Park, p. 4.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, p. 221.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, p. 224.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, p. 218.

Thomas Chapais, speech delivered at the monument’s inauguration on September 1, 1938. From Jean Provencher, Jean Du Berger, Jacques Mathieu, “A Citizen’s Park,” in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl dir., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the ideal, p. 266.

In 1899, when Great Britain declared war on South Africa’s two independent Boer republics, Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain looked to Canada, among others, for military support. While English Canadians naturally felt that they should help the motherland, Francophone nationalists, led at the time by Henri Bourassa, believed that Canada must remain independent and aloof from England’s conflicts.

Biography taken from Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, The Natural Park, p. 218.

Built Heritage

Observatory

In order to find their way at sea, one of the essential pieces of information needed by mariners is knowledge of the exact time. Before the development of telecommunications and modern navigation instruments, this information was gained by astronomical observation. In Quebec City, to assist the many navigators anchoring at the port each year, an astronomical observatory was built in 1850 at the Citadel. It was completed in 1854-1855 and was placed under the responsibility of Lieutenant Edward David Ashe, who continued working there until 1864.

A time ball, functional from 1852 onward, was used to indicate the time. Situated clearly in view on the roof of the Observatory, the ball was raised to the top of the tower at 12:55 p.m., a sign that observers must prepare to synchronize their watches. At exactly 1 p.m., the time ball was dropped. This was how the public and mariners could know the right time any day during the navigation season, except Sundays.

Astronomical observations began to be conducted in part on the Plains beginning in 1864. The Observatory obtained an equatorial telescope and installed it in a tower surmounted by a dome. This tower is situated on the property occupied by the Bonner Farm, close to what are now the Edwin Bélanger Bandstand and the Centennial Fountain. The work carried out there enabled Commander Ashe to observe and photograph solar eclipses and sunspots.

The Observatory, when the park’s avenues were being laid.

Credit: Archives de la ville de Québec.

After Confederation, the Quebec City Observatory became the responsibility of the Department of Marine and Fisheries. In 1873-1874, the remainder of the equipment was transported to the Plains where, since 1864, the telescope has been located. The time ball is still at the Citadel, visible from the port. It is now activated remotely from the Plains Observatory.

Along with the equipment, the Director of the Observatory himself moved to the Plains. A residence attached to the observation tower became the home of Commander Ashe and his family. He was succeeded after his death by his son, William Ashe, who held the position of Director of the Quebec City Astronomical Observatory from 1866 to his death in 1893. He was replaced in 1894 by Arthur Smith, who lived in the residence until 1930.

With the 20th century and the development of telecommunications and transportation, navigation came to depend less on astronomical observations. Meteorology became the most important aspect of the job of Director of the Observatory. After the retirement of Arthur Smith in 1930, the Observatory became a weather station. It was directed by Maurice Royer who, like his predecessors, lived with his family in the residence attached to the station.

The Observatory was demolished in 1936 and some of the instruments were transferred to the Collège des Jésuites. The weather station was moved to the corner of Laurier and Taché streets (close to Martello Tower 2) and remained there until 1954, when the weather service began operating out of the airport.

The scientific tradition on the Plains continued when, in the early 1940s, the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (Quebec City Centre), with the collaboration of the National Battlefields Commission, installed an Observatory surmounted by a cupola in Martello Tower 1. It was open to the public and received some 14,000 visitors over the decade. This public education mission continued until 1962 and was then taken up again in 1994, this time at Martello Tower 2, where activities for the public and an exhibition were available.

Finally, in the summer of 1987, to commemorate the Observatory and the scientific vocation of the Plains of Abraham, a sundial was inaugurated close to the original site of the Observatory.

Sundial.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Jail - 1867-1970

In the middle of the 19th century, it was decided that the Quebec jail situated inside the walls of the city (what is today the Morrin Centre) was no longer adequate, and that a new one would be built on the Plains of Abraham in September 1861. The plans prepared by architect and engineer Charles-Philippe-Ferdinand Baillargé (1826-1906) made it the first prison in Canada constructed in accordance with the principles of sanitation and the most recent theories on penitentiary systems.

The first inmates were put in the prison in 1867. Until the early 1930s, both women and men were held there. The Gomin house in Sainte-Foy became the women’s prison in 1931. In all, the prison had 138 cells in two wings when it opened. In summer, the inmates work on a farm adjacent to the prison.

The state of the park before it was landscaped in 1907; left, the Observatory; right, the prison.

Credit: LAC

Despite its avant-garde design, the prison stood as an impediment in architect Frederick Todd’s development plans. In 1909, he recommended the demolition of this austere building that undermined the recreational vocation it was hoped the park would have. His recommendation was rejected, but in 1911, the Quebec government did agree to cede to the National Battlefields Commission a portion of the land surrounding the site.

The prison housed its final occupants in 1967 and was decommissioned in 1970. For a period of time in the early 1970s it served as a youth hostel nicknamed the “little Bastille.” An integral part of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec since the 1980s, the prison was named Pavillon Charles-Baillargé and was used to house the museum’s exhibitions. The building was classified a historic monument in 1997 by the Quebec government.

Quebec Skating Rink - 1891-1918

Starting in the 1877, the Quebec Skating Club began operating a rink on the north side of the Grande Allée, just outside the ramparts. When the Parliament was being built, the Club had to move because it interfered with the Parliament Hill development plans. The Quebec Skating Rink was then constructed in 1891 on the other side of the Grande Allée, within the present confines of the Plains of Abraham, where the Cross of Sacrifice now stands.

The Quebec Bulldogs hockey team played a number of its games and in fact won the Stanley Cup in 1911-1912 and 1912-1913 on this rink. The building was also used by Laval University students and by intermediate and junior league teams. Fairs and exhibitions were staged there during the summer.

The future of the skating rink was called into question when the Battlefields Park was created in 1908, since this was where the park’s planned main entrance would stand. Negotiations were unsuccessful, and the club kept the land. The building was destroyed by fire in 1918, but the property was not acquired by the Commission until 1933.

The Quebec Skating Rink stood where F.G. Todd had planned to create the main entrance to the Plains of Abraham.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Arsenal - 1884-1938

A cartridge factory was built by the federal government within the city walls in 1879. To minimize the consequences of an accidental explosion, part of the factory was moved to the foot of the Citadel in 1884, on what was then called Cove Fields. The factory was composed of a series of wooden buildings surrounded by palisades isolated one from another by earthen ramparts in order to limit damages should a conflagration occur. A firing range was also set up to control the quality of the ammunition. Since Cove Fields was destined to become a part of the Battlefields Park, the Arsenal was moved to the Saint-Sauveur district in 1912.

In 1885, the Quebec City Arsenal produced the ammunition used by the Army fighting the Métis in the West. In two months, 1.5 million cartridges were produced, primarily by women employees. In 1901 the Cartoucherie de Québec saw its name changed to Dominion Arsenal. During World War I, the Arsenal had up to 900 employees.

Like the jail, the skating rink and the remains of the Ross Rifle Company, the Arsenal stood in the way of the development of the Battlefields Park. The National Battlefields Commission claimed the Cove Fields, and although the Arsenal buildings had become obsolete with time, they were not demolished until 1939, when cartridge production was transferred to the Valcartier military base.

The Arsenal laboratory on the Plains of Abraham; background right, the Quebec Skating Rink.

Credit: LAC.

Ross Rifle Factory - 1902-1931

In 1902, Scottish industrialist Charles Ross built a factory on the Plains of Abraham where the water reservoir now stands, close to Martello Tower 1. Thousands of rifles, used to equip Canadian Army soldiers until the beginning of World War I, were produced there. The Ross Rifle was retired from service in 1916. Although said to be very accurate, it was known to jam occasionally and discharge in the shooter’s face.

The Ross Company was expropriated by the federal government in 1917 and ceased its activities. An unsuccessful attempt was made to retool after the closing of the factory on the Plains. The National Battlefields Commission obtained the land of the Ministry of Defence and the Ross Rifle Company (Cove Fields) in 1928, but had to wait until the Army relocated elsewhere before demolishing the buildings. They were being used for military stores even in the 1930s, but were destroyed to make room for the Quebec City water reservoir in 1931.

The Ross-rifle factory, in the heart of Cove Fields, in 1925.

Credit: Archives de la ville de Québec.

Interior view of the Ross-rifle factory around 1905.

Credit: LAC.

Municipal reservoir– 1931-1933

In 1930, the Quebec City Council and the National Battlefields Commission pressed the federal government to demolish or move the remainder of the Ross Rifle Factory, now being used for military stores, in order to begin the construction of a drinking water reservoir. In addition to improving the water supply system and increasing fire protection, this was one of many projects started by municipalities to provide work for the hordes of unemployed in the Depression of the 1930s. Apparently, in order to give work to as many people as possible, the city wanted all the digging to be done by hand, with shovels. On its part, the National Battlefields Commission did not wish to see anything added to the park that would mar its appearance.

The reservoir was built between 1931 and 1933. Its base lies about two metres under the surface of the Plains, and it contains about 136 million litres of water. Situated on one of Quebec City’s highest points, it provides drinking water to the districts of Saint-Roch, Saint-Sauveur, Champlain and parts of Saint-Jean-Baptiste and Limoilou. Its vault is supported by some 900 columns and surmounted by about 20 supply grilles camouflaged by bunches of shrubs.

Construction of the municipal reservoir in 1932.

Credit: Photo by W.B. Edwards, Archives de la ville de Québec.

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec – 1933

The idea of building a museum on the Plains as part of the tricentennial celebration program was put forth even before the creation of the park. Nothing was done until 1922, when the provincial government expressed its intent to build a museum on the Plains, close to the prison, on a property that had belonged in part to the Commission since 1911.

The plans of architect Wilfrid Lacroix proposing a “Beaux-Arts” style of building were accepted. The Quebec Provincial Museum opened its doors in 1933, at which time it housed the Quebec Archives and the natural science and fine arts collections. The building was named “Musée du Québec” in 1961. The archives were transferred to the campus of Laval University in 1979, and, beginning in 1983, the collection consisted solely of artworks. The prison was restored from 1989 to 1991 and became an integral part of the museum. The Grand Hall was added in 1991, providing a link between the Gérard-Morisset and Charles-Baillargé buildings. In 2002, the building’s name was again changed, this time to Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

Soldiers’ huts; prison camp; faubourg de la misère – 1940-1952

The outbreak of war in 1939 put a halt to major improvements to the park. At the same moment, military authorities built 40 huts in Cove Fields to house soldiers waiting to ship out to Halifax on their way to Europe and the front. The British Army however lost no time in commandeering them for use as a prisoner-of-war camp. One of Canada’s lesser known contributions to the war effort was as host to 35,000 German prisoners in 20 camps between 1940 and 1946.

The one on the Plains was called Camp L, or Cove Fields Camp. It opened in July 1940 with 793 inmates. The majority of those interned were German civilians, mostly Jews who had fled to England and were considered untrustworthy by the British government. There were also 90 prisoners of war—German aviators and sailors.

Camp L was only open for 3 months because it failed to meet any of the security standards. It was close to the city. Civilians—tourists included—could get close to it. Prisoners even passed notes to civilians outside. Security measures were meagre and a mass escape could easily have occurred. There was a fence topped with barbed wire, but it could have easily been climbed. There were no floodlights. Guards were lightly armed and ill trained. Guard duty had been assigned to the Trois-Rivières Regiment, which had 11 officers and 172 soldiers of various ranks. Quarter-guards were made up of 23 soldiers, including 7 sentinels. Days were long and there were no jobs for the internees to do. The camp was shut down in fall 1940 and its prisoners reassigned to other camps, after which the huts resumed duty as temporary lodgings for Canadian soldiers.

In 1945 a serious housing shortage in the city left many families on the streets. With permission from the federal government, municipal authorities rented 20 of the huts to provide temporary accommodations to several families. By fall there were 40 of them. A school and chapel arrived the following year. The population of what became known as the slum quarter (“faubourg de misère”) continued to increase as it grew increasingly dilapidated, compromising the look of the park. The authorities faced a dilemma. They wanted to get rid of the miserable shacks marring the landscape and putting off the tourists, but they were reluctant to throw needy families back out in the street. So one by one the city found them new homes, and by 1949 the Commission started getting rid of the buildings as their inhabitants departed. In 1950 a housing cooperative arranged for the relocation of more families to other neighbourhoods. Other huts were dismantled and the materials used to build new houses near Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde Church. The last occupants of the slum quarter were served with an order to vacate the premises by May 1, 1951.

The military barracks, a village for the poor on the Plains of Abraham between 1945 and 1952.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Greenhouses

In 1915, landscape architect Frederick G. Todd submitted a sketch and a plan to the Commission for the construction of a greenhouse:

[…] the Commission will be better able to raise the different varieties and quantities of flowers required for the ornamentation of the Park and have these whenever they are needed – flowers cannot very well be supplied by florists in large quantities at a low price at any time – and further that a greenhouse will ensure the raising of healthy stock and avoid the costs and risks of transportation of the plants.

The first greenhouse was built in 1916-1917; its length was doubled in 1917. In 1938, a new greenhouse, smaller than the first one, and an office were built to the north of the original buildings. In 2017, the small greenhouse is demolished for security.

The greenhouse team grows some 45,000 plants and 150 varieties including tuberous begonias, marigolds, pinks, petunias, ageratums and alyssums, along with unique varieties.

The Plains of Abraham Greenhouses.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Workshops

A few shops were built in 1912 to assist in park maintenance. In 1918, the Superintendent suggested erecting service buildings throughout the park, some of them alongside the greenhouses. This was only a temporary solution, and less than 10 years later, in 1927, the existing building, which serves as a garage, storage depot and workshop, was built. Since that time, the workshops have been renovated and modernized to adapt to the modern equipment used in maintaining much of the Plains’ property and infrastructures

390 de Bernières

In 1909, the year after its inception, the National Battlefields Commission leased the second floor of a house on Cook Street for its offices. When the lease expired in 1924, the Commission moved to the fifth floor of 71 rue St-Pierre. In the 1940s, the Park administration moved to 390 rue de Bernières, close to Martello Tower 2. The building, with stone covered walls, turret and copper roof, was built in 1940 and was renovated in 1982 and 1984. In 2018, the Park administration moved to the Plains of Abraham Museum, 835 Wilfrid-Laurier Avenue.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Pavilion (Services building)

The Plains Services Building is situated in the heart of the Park, close to the Edwin-Bélanger Bandstand, the Centennial Fountain and the Sundial. It was built in 1995 to respond to the needs arising from the increased activities in the sector, in particular performances staged at the Edwin-Bélanger Bandstand. The building contains washrooms, storage, a skiers’ rest stop and a restaurant, along with the park’s cultural and technical services.

The Plains of Abrahams service pavilion.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Edwin-Bélanger Bandstand

Construction of the bandstand started in the fall of 1992; it was inaugurated the following year. The bandstand lies at the centre of the Plains and is a permanent venue for jazz, blues, pops and world music. Between 50,000 and 60,000 visitors, or more than 1, 000 per concert, attend from June to August. .

The bandstand is named after violinist, conductor and musician Edwin Bélanger (1910-2005), who was one of the founders of the Cercle philharmonique de Québec in 1935. From 1937 to 1961, he directed the Musique du Royal 22e Régiment. He was also artistic director of the Quebec Symphony Orchestra from 1942 to 1951.

The Edwin-Bélanger Bandstand.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Plains of Abraham Museum

This pavilion was built in 1938-1939 by the Department of National Defence to accommodate the Dominion Arsenal munitions inspection service until after World War II. The inspection service shared the facilities after May 1947 with the Royal Canadian Navy, which ended up occupying the whole building.

The building was named HMCS Montcalm, after the local Naval Reserve. The Canadian Naval Reserve was created in 1923 to train volunteers on naval vessels (HMCSs) attached to land bases.

Situated right next to the Grande Allée and the Québec Armoury, the building is the work of Quebec architects Ludger Robitaille and Gabriel Desmeules. It harmonizes with the military barracks, designed in 1887 by Eugène-Étienne Taché, and is inspired by the architecture of the Loire castles. On March 5, 1992, the Federal Heritage Building Review Office recommended giving the building historic monument status.

Management of the building was handed over to the National Battlefields Commission on May 28, 1996, the Naval Reserve having moved to the Old Port of Quebec in 1995. The Commission inaugurated the Discovery Pavilion in the spring of 1998 to enhance the visitor experience. In 2014 on the occasion of the building’s 75th anniversary, it was renamed the Plains of Abraham Museum. Aside from the permanent exhibitions, the building provides reception, information, toilets, wifi, route headquarters in season, and souvenir shop.

The Plains of Abraham Museum.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Paulette Smith-Roy, L’observatoire astronomique de Québec, 1850-1936, Quebec City, National Battlefields Commission, 1983, p. 15.

Paulette Smith-Roy, L’observatoire astronomique de Québec, 1850-1936, p. 27.

Archives of the National Battlefields Commission, Paul-H. Nadeau, Mémoire à la Commission des champs de bataille nationaux, Quebec, Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Quebec City Centre, November 15, 1951.

Lucie K. Morisset, Le Musée du Québec: trois architectures, Québec, [n.p.], 1991, p. 26.

Suzanne Bernier, Concept de mise en valeur de l’ancienne prison de Québec (Édifice Baillargé), Québec, Direction du patrimoine, 1989, p. 42.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden, in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery, Septentrion, 1993, p. 237.

La prison des Plaines d’Abraham, Québec, Ministère des Affaires culturelles, 1978, p. 14.

Gouvernement du Québec, Ministère de la Culture, des Communications et de la Condition féminine, Répertoire du patrimoine culturel, [http://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca], (page consulted November 23, 2007).

Parks Canada, Les travailleurs de l’Arsenal de Québec, 1879-1964. Photos et témoignages, Ottawa, Parks Canada, 1980. p. 8.

Parks Canada, Les travailleurs de l’Arsenal de Québec, p. 11.

Pierre Asselin, “Un mystère résolu 73 ans plus tard,” Le Soleil, December 27, 2005, p. A12.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 234.

Denis Bolduc, “Réservoir d’eau spectaculaire et parfaitement conservé,” Journal de Québec, November 10, 2005, p. 5.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden,” in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 232.

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, About the Musée. Background, [http://www.mnba.qc.ca/Afficher.aspx?page=1119&langue=en], (page consulted on November 23, 2007).

Yves Bernard and Caroline Bergeron, Trop loin de Berlin : Des prisonniers allemands au Canada (1939-1946), Quebec City: Septentrion, 1995, p. 17.

Claude Paulette and Jacques Mathieu, “The Natural Park: A Romantic Garden”, in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 237.

Archives of the National Battlefields Commission, minutes of Board of Directors Meeting, August 10, 1915.

Archives of the National Battlefields Commission, René Castonguay, Historique de certains édifices du Parc des champs de bataille, Quebec City: [National Battlefields Commission, 1990, p. [2-3].

Cécile Huot, “Bélanger, Edwin,” Encyclopedia of Music in Canada, [http://thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=Q1ARTQ0000255], (November 23, 2007).